Marion Blumenthal Lazan: A Survivor’s Story

April 24, 2018 — Marion Blumenthal knew the war was over when the soldiers guarding her train started looking for civilian clothes to change into. She, her family, and hundreds of other starving and ill Holocaust survivors had been on that crowded death train for two weeks without access to food, water, or sanitation. They were somewhere in Germany, headed east, when they were liberated by Russian troops. Marion was 10 years old, and she weighed 35 pounds.

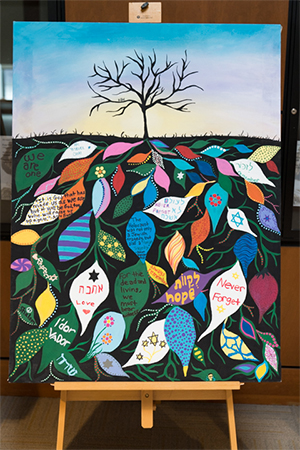

Marion Blumenthal Lazan was on campus on April 10 to serve as the keynote speaker for Marist’s 28th Annual Holocaust Remembrance in the Nelly Goletti Theatre. Blumenthal Lazan’s talk was entitled “Four Perfect Pebbles: My Holocaust Story,” and its goal was to share “a message of perseverance, determination, faith, and hope.” The program also featured a musical performance by Thomas Muratore ’21, who played the theme from Schindler’s List accompanied by Adjunct Instructor of Music Elena Pelih. The evening ended with the lighting of memorial candles to remember the millions lost in the Holocaust. On display outside the Theatre was artwork by students in Marist’s Hillel.

Blumenthal Lazan was a small child in Germany when she and her family became victims of the Nazi regime. Her well-to-do family never expected what was to come, particularly not her father, who had received an Iron Cross for his military service during World War I. But with the implementation of the 1935 Nuremberg laws, Jews were essentially banned from public life – they were fired from government jobs and denied access to public schools, parks, and theaters. They were subject to an evening curfew and had a “J” stamped on their passports. Non-Jews were forbidden from shopping at Jewish-owned stores.

In 1938, her grandparents passed away, and the family obtained papers to emigrate to the United States. Blumenthal Lazan was four years old. But in November of that year came Kristallnacht, the “Night of Broken Glass” in which Jewish homes, businesses, and synagogues all over Germany were destroyed. Her family’s apartment was ransacked, and her father spent three weeks in Buchenwald. Selling their home and business, the family fled to Holland to await passage to America. That journey never took place because in December 1939, the family was deported to the infamous Westerbork prison camp, and in May 1940, one month before they had intended to leave Europe, the Germans invaded Holland. They were trapped.

In early 1942, the transports to death camps in the east began, and by 1944, it was the Blumenthal family’s turn. Of the 120,000 men, women, and children deported from Westerbork, 102,000 never returned. With one knapsack each, Blumenthal Lazan and her family joined other Jews crammed into cattle cars on a bitter cold and rainy January night. She was nine years old and on her way to Bergen Belsen.

Separated from her father and brother Albert, Blumenthal Lazan was fortunate to share a bunk with her mother in unheated barracks built for 100 but housing 600. She credits her survival to her mother’s sheer willpower. They had nothing but a thin blanket and slept on a straw mattress. With no privacy or soap, little water, and a meager daily ration of bread and turnips, conditions were bleak. Malnutrition, dysentery, and typhus were all rampant, and the filth and odor were pervasive. And with wagons filled with dead bodies passing by, fear was a constant. Observed Blumenthal Lazan, “We had a shower once a month. And since everyone at that point knew about the extermination camps, we never knew whether there would be water or gas coming out of the shower heads.”

Under such conditions, many lost the will to live, and Blumenthal Lazan noted, “I saw things that a child shouldn’t have to see.” Nonetheless, she passed the time by using her imagination, making up games like the four pebbles, which later provided the title of her memoir. In her mind, if she could find four similar-sized pebbles in the camp, it meant that she, her parents, and her brother would all survive the war. It gave her hope for better days ahead. In another game, she would find a piece of glass, and the light reflected on the ground became her pet. Looking back, she came to realize that “these imaginative games were my survival.”

Fast forward to the end of the war. The Allies are closing in, and Blumenthal Lazan and her family are on a crowded train in which one in five passengers had died. Sick with typhus, she also had a burned leg that was severely infected. When the train was liberated, the survivors exited and took over the abandoned homes of those who had fled the Russian advance. Fortunately, Blumenthal Lazan’s leg was treated and saved. Unfortunately, her father succumbed to typhus six weeks after liberation.

The displacement of war brought Blumenthal Lazan, her mother, and brother back to Holland, where she became reacquainted with life at the age of 11. “I had never been in a store and had no table manners,” she recalled. Originally intending to emigrate to Palestine, she began her formal education in a Montessori school, learning both Dutch and Hebrew. In April 1948, her life changed when her family was able to use their boat tickets from 10 years earlier to sail to America. On April 23, 1948, the family arrived in Hoboken, New Jersey and settled in Peoria, Illinois, where they were welcomed warmly. At 13, Blumenthal Lazan started learning English, her third new language after Dutch and Hebrew. Always an optimist, she also turned out to be a brilliant student, eventually graduating eighth in her high school class. She soon married Nathaniel Lazan – the couple will celebrate 65 years of marriage this August – and they have three children, nine grandchildren, and 4 great-grandchildren.

It took Blumenthal Lazan 30 years to talk about her wartime experiences. She said, “In order to go on, we had to set it aside.” In 1995, she went back to Germany for the first time to visit her father’s grave. The next year, she published her memoir, Four Perfect Pebbles, which has since been translated into such diverse languages as Hebrew, German, Dutch, and Japanese. She is also the subject of a documentary film, Marion’s Triumph, narrated by actress Debra Messing.

Blumenthal Lazan closed her presentation to the Marist community by asking the audience for a favor: “I ask this generation to please share my story. When my generation is gone, you will have to bear witness.” She held up the old yellow Star of David she had to wear on her clothes. “Each one of us must prevent this from reoccurring, and respect for one another starts at home. Look for the similarities in people and respect the differences. Never generalize and judge an entire group. Be kind and good and respectful, and there will be peace in the world.”